By Dennis OverbyeSept. 27, 2019

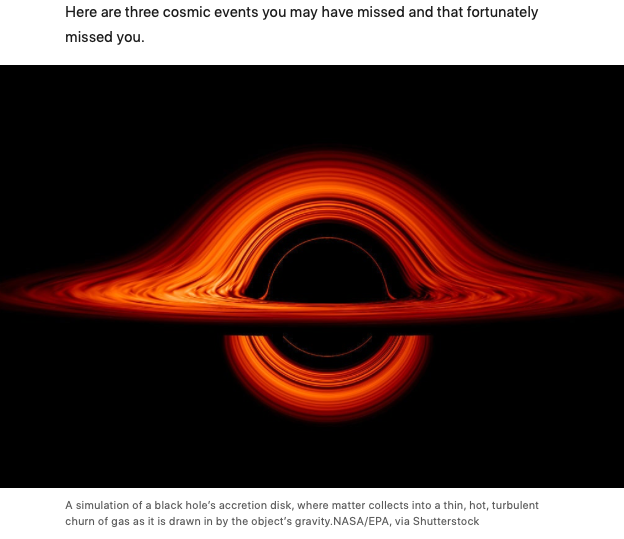

With everything else that has been going on lately down here on this planet, you might not have noticed that there has been a lot of news lately about black holes, those Einsteinian monsters that can swallow light and everything else, behaving badly. Black holes eating stars, or whole gangs of them. Black holes burping energy from the centers of galaxies. Black holes banging together in universe-shaking events.

It sounds like cosmology according to Stephen King. Over the summer I was on a lake in Peru, where the water was boiling with feeding piranha, their little black fins furiously breaking the surface. I was safe in the boat. Then.

Turns out that it has been Black Hole Week, complete with its own hashtag, according to NASA. “I think they wanted to highlight all of the black-hole work that NASA telescopes have done and are doing, and combine it into a weeklong social-media event,” Peter Edmonds, a spokesman for the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and the Chandra X-ray Observatory, wrote in an email.

Indeed, telescopes on the ground and in space, scanning the sky in everything from X-rays to radio waves, have combined to tell some scary stories. Here are a few to get you in the mood.

With their sights set relatively close to home, astronomers from the University of California, Los Angeles, reported this month that the giant black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy had become inexplicably hungrier.

The black hole, the abyssal grave of about 4.3 million suns worth of mass, usually emits a dull radio glow as gas and dust swirl in and heat up. This summer, however, it got so hot and bright that the astronomers mistook it for a real star.

Andrea Ghez, a U.C.L.A. astrophysicist who has long monitored the object, which is known as Sagittarius A*, had never seen it so bright. “It’s usually a pretty quiet, wimpy black hole on a diet,” she said in a news release. “We don’t know what is driving this big feast.”

Maybe it swallowed an asteroid, or shredded and finally swallowed gas from a double star called G2 that passed close to the black hole in 2014. What Is a Black Hole? Here’s Our Guide for EarthlingsWelcome to the place of no return — a region in space where the gravitational pull is so strong that not even light can escape it. This is a black hole.April 10, 2019

The shredded star

Peering farther out, other astronomers spotted a black hole destroying and shredding a star in distant galaxy. It happened in January, in full view of a pair of NASA’s space-based eyes — a robotic telescope in South Africa that is part of a network called the All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae, or ASASSN (which is pronounced “assassin”).

Tom Holoien, of the Carnegie Observatories was surveying the sky as part of his work for the network from a telescope in Chile. He saw the sudden flash in a galaxy that lies 375 million light-years away behind the constellation Volans in the far southern sky.

Dr. Holoien alerted the operators of NASA’s Swift satellite, which monitors X-rays from violent high-energy events, and NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS, which happened to be staring at that part of the sky looking for the blinks in starlight caused when exoplanets pass in front of them. As a result, TESS recorded the entire event in the background of its planet search.An animation simulating the destruction of a star by a supermassive black hole at the center of a galaxy 375 million light-years from here.

Gradually the astronomers realized that the flash wasn’t behaving like a supernova but rather like a tidal disruption event. In such a calamity, a star that wanders too close to a black hole experiences intense tidal forces that pull it apart. The star is reduced to spaghetti-like streams of gas that circle the black hole. Some gas eventually falls in and disappears, but a lot of it is tossed free and crashes into other gases. “It’s a messy process, where a lot of gas is flying in different directions at high speeds,” Dr. Holoien said.

Astronomers have seen this happen about two dozen times in other distant galaxies, but so far not in our own, Dr. Holoien said. He described the January event as a “poster child” for black-hole shredding. The mass of the object is about 6.3 million times greater than that of our sun, making it slightly more massive than the black hole squatting at the center of the Milky Way.

“We don’t know as much about the star,” Dr. Holoien said, although he says that it was probably “pretty similar to our sun.”

Apocalypse later

If there are any astronomers to be found in a faraway trio of galaxies collectively called SDSS J084905.51+111447.2, they likely are anxiously anticipating a display of fireworks that will unfortunately end their own existence. The three galaxies are circling each other in the slow dance of merging, and each harbors a supermassive black hole at its center. These gigantic, wheeling behemoths of nothing are on course to collide in about 1 billion years.

[Sign up for the Science Times newsletter for stories that capture the wonders of nature and the cosmos.]

Such a collision would rattle the bones of the cosmos and could shake apart nearby matter. One of the black holes is 460 million to 2.9 billion times more massive than the sun, according to radio and X-ray measurements, said Ryan Pfeifle of George Mason University and the lead author of a recent paper about the galaxies.

The galaxies and their dense black hearts currently lie about 30,000 light-years apart, at least as viewed from Earth, which is about 1 billion light-years from the action. But nobody really knows what will happen when they get closer to one another.

“Not all galaxies that appear to be ‘merging’ will actually end up ‘fully’ merged,” Dr. Pfeiple said in an email. “Sometimes you have flyby interactions that look like an ongoing merger, but the galaxies never actually merge.”

One likely possibility is that gravitational forces between the holes will fling one of them away, leaving the other two closer and more likely to collide.

“I would say at this point it is anyone’s guess as to which, if any, of the black holes will be sling-shotted out,” Dr. Pfeiple wrote. “Simulations in the literature predict that it should happen when you have three supermassive black holes interacting.” But without more data on the orbits and energies of these objects, he added, it was impossible to predict how, when or if the apocalypse would happen.

A collision between two or three supermassive black holes could light up gravitational wave detectors on Earth.

Make every week Black Hole Week

In September of 2015, those observatories gave Einstein his greatest moment in a century when they recorded space-time ripples emanating from the collision of a pair of black holes. The data agreed perfectly with his prediction that enough matter and energy in one place would sink together endlessly, wrapping space and time like a glove around it — a black hole.

LIGO and its ilk have made clear that the universe is full of these beasts rumbling and bumping around in the dark. After a brief rest, the twin LIGO antennas and their European relation, VIRGO, resumed sentry duty this spring. Their watch has paid off.

Last spring I downloaded a smartphone app called Gravitational Waves Events, which sends an alert every time LIGO or VIRGO detects a presumed gravitational wave. The alert arrives as a short chirp, the characteristic signal produced by a pair of colliding black holes as they speed up in the last seconds of their marriage.

It’s gone off some four dozen times since April. Sometimes I hear it in my sleep.

Of course, black holes don’t roam the universe like vampires looking for victims. They are as lazy as they are fat. They eat what the winds and currents of space and the dance of gravity bring to them.

But that can be a lot. The more that astronomers learn about the universe, the more it seems that what goes around comes around, whether in the form of meteoroids from Mars or interstellar comets from other stars. Oblivion is random. The issues raised by black holes, of what might be delicately called the Ultimate State — whatever it is that happens when you hit the bottom of a black hole — are always with us.

Be afraid, be very afraid. I hope you enjoyed Black Hole week.