Aryn Baker of TIME Magazine

It’s just after 7 in the morning in the Pakistani city of Jacobabad, and donkey-cart driver Ahsan Khosoo is already drenched in sweat. For the past two hours, the 24-year-old laborer has been hauling jugs of drinking water to local residences. When the water invariably spills from the blue jerricans, it hits the pavement with an audible hiss and turns to steam. It’s hot, he agrees, but that’s not an excuse to stop. The heat will only increase as the day wears on, and what choice does he have? “Even if it were so hot as if the land were on fire, we would keep working.” He pauses to douse his head with a bucket of water.

Jacobabad may well be the hottest city in Pakistan, in Asia and possibly in the world. Khosoo shakes his head in resignation. “Climate change. It’s the problem of our area. Gradually the temperatures are rising, and next year it will increase even more.”

The week before I arrived in Jacobabad, the city had reached a scorching 51.1°C (124°F). Similar temperatures in Sahiwal, in a neighboring province, combined with a power outage, had killed eight babies in a hospital ICU when the air-conditioning cut out. Summer in Sindh province is no joke. People die.

To avoid the heat, tractor drivers in this largely agricultural area till the fields at night and farmers take breaks from noon to 3, but if life stopped every time the temperature surpassed 40°C (104°F), nothing would ever get done. “Even when it’s 52°C to 53°C, we work,” says Mai Latifan Khatoom, a young woman working in a nearby field.

The straw has to be gathered, the seeds winnowed, the fields burned, the soil turned, and there are only so many hours in the day. She has passed out a few times from the heat, and often gets dizzy, but “if we miss one day, the work doesn’t get done and we don’t get paid.”

If the planet continues warming at an accelerated rate, it won’t be just the people of Jacobabad who live through 50°C summers. Everyone will. Heat waves blistered countries across the northern hemisphere this summer. In July, all-time heat records were topped in Germany, Belgium, France and the Netherlands. Wildfires raged in the Arctic, and Greenland’s ice sheet melted at a record rate. Globally, July was the hottest month ever recorded.

Climate scientists caution that no spike in weather activity can be directly attributable to climate change. Instead, they say, we should be looking at patterns over time. But globally, 18 of the 19 warmest years on record have occurred since 2001. I asked Camilo Mora, a climate scientist at the University of Hawaii at Manoa who in 2017 published an alarming study about the link between climate change and increased incidences of deadly heat waves, if this was the new normal for Europe. He laughed. The new normal, he says, is likely to be far worse. It’s likely to look something like Jacobabad.

Scientists estimate the probable increase in global average temperature will be at least 3°C by the end of the 21st century. That, Mora says, would mean three times as many hurricanes, wildfires and heat waves. People won’t be able to work outside in some places, and there will be increased cases of heatstroke, heat-related illness and related death. In the U.S., extreme heat already causes more deaths than any other severe weather event, killing an estimated 1,500 people each year.

A 2003 heat wave in Europe is estimated to have caused up to 70,000 deaths. Yet we still don’t think of heat as a natural disaster on a par with, say, an earthquake, or even akin to a terrorist attack, says Mora. “Heat kills more people than many of these disasters combined. Europe [in 2003] was like a 9/11 every day for three weeks. How much more disaster do you want before we start taking it seriously?”

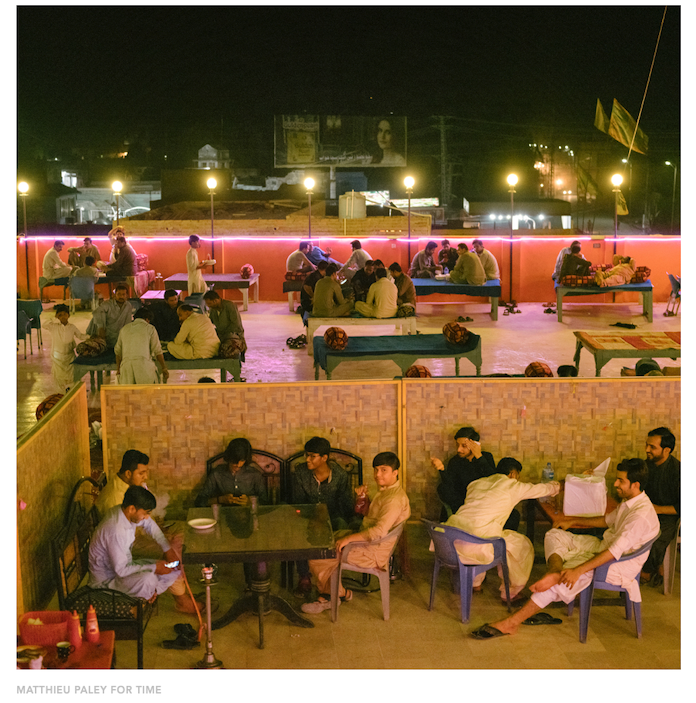

“If you want to report on heat, this is the right place to be,” Anees, a security guard working for my hosts in Jacobabad, cheerfully informs me as I arrive on a scalding June afternoon. Pakistan holds the heat record for Asia, he says proudly, though he has heard that it gets hotter elsewhere. It does, but the world’s highest recorded temperatures—in California’s Death Valley, for example—usually occur far from human habitation. Urban enclaves, where dense construction, a lack of green space and traffic congestion combine to create a heat-island effect, are rapidly catching up.

While Pakistanis regularly claim Jacobabad as the hottest city in the world, it depends on how you measure it. Various atmospheric-science organizations use different metrics, and record-breaking highs have ping-ponged between Iran, Pakistan and Kuwait over the past couple of years. After extensive research, the World Meteorological Organization announced earlier this year that Turbat, Pakistan, 900 km (560 miles) to the southwest, could claim the title with a temperature of 53.7°C (128.7°F) on May 28, 2017. Jacobabad may very well win the endurance round, though, regularly surpassing 50°C (122°F) in the summer months.

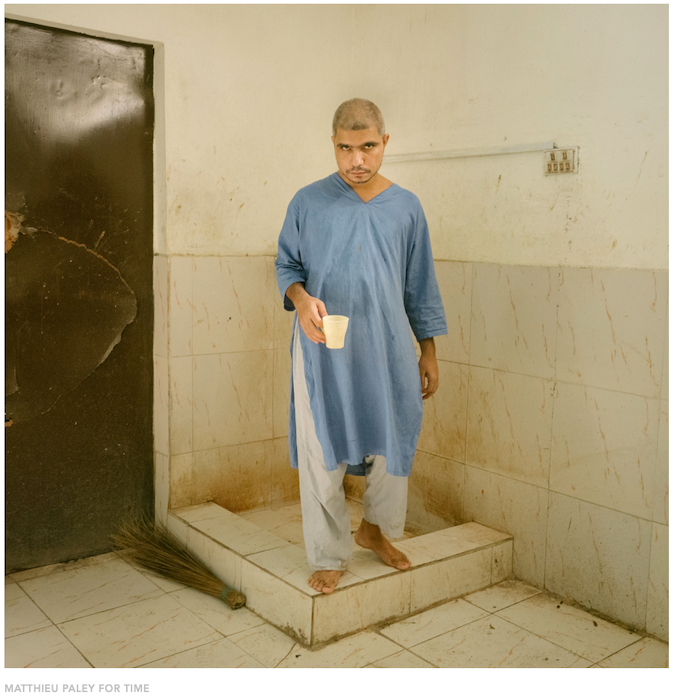

Most days, the Jacobabad district, population 1 million, suffers from power outages that can last as long as 12 hours. Even when there is electricity, few households can afford an air conditioner. Locals rely on traditional remedies, like thadel, a supposedly cooling tonic made from ground poppy seeds mixed with spices, rose-flavored syrup and iced water. They also dress right for the weather, the women wearing shalwar kameez suits made of cotton lawn, a light, airy fabric. The loose trousers billow out from the waist, the long-sleeved tunic protects the arms, and a scarf covers the head. The men wear something similar, though without the vibrant patterns.

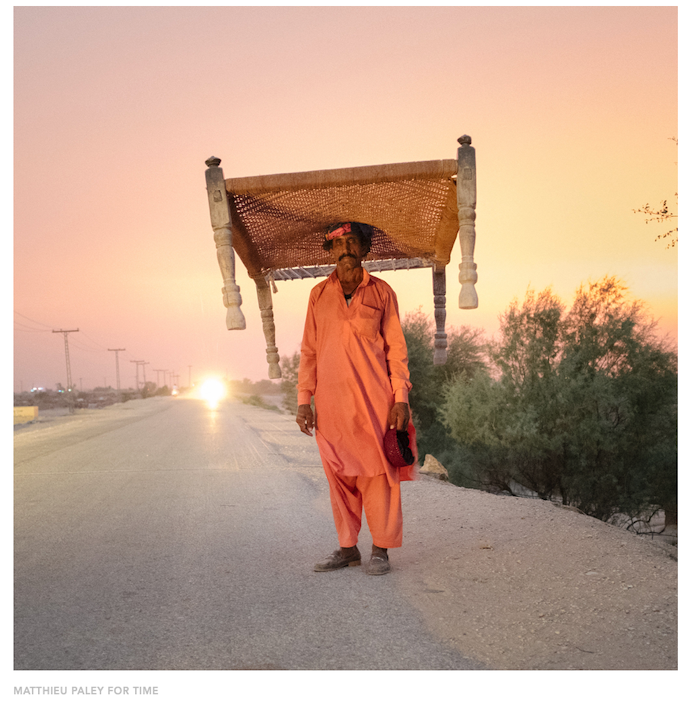

Khosoo, the donkey-cart driver, soaks his clothes in water several times a day, while tractor driver Nabi Bux swears that the Sindhi pop tunes blaring from his open cab take his mind off the heat. Sixty-something Mohammad Ayub, who sports a red cap sprinkled with tiny winking mirrors in the traditional Sindhi style, recommends taking frequent rests under a tree. The only problem is that most of the trees in the area have been chopped down for firewood. “Sometimes, when it gets above 52°, I feel like my brain is rolling around in my head.” It was never that hot when he was a child, he complains. “We had more trees then. Now the trees are gone.”

The only real remedy, says a local doctor, Abdu Hamim Soomro, is to stay hydrated and get out of the heat. Thadel is pure superstition, he says. Still, he drinks it. “Maybe it’s the opium from the poppy seeds,” he jokes. “It makes us feel better, and everyone is addicted to it.”

Not even the night air offers much respite. The digital thermometer I had been carrying around with me registered 41.1°C (106°F) at 10 p.m. Instead of mattresses, most people sleep on charpoys—low cots of woven leather that allow the air to circulate underneath the body. The solar panels that run fans during the day don’t work at night. Khosoo is one of the lucky ones; at night he puts his donkey back to work, treading a circle that powers his ceiling fan. But someone has to stay awake to keep the donkey going, he says, so either way, nights are rarely restful in the summer months.

What seems like the minor inconvenience of a restless night has widespread ramifications, however. Nick Obradovich, a research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Lab, started looking at the mental-health impact of climate change when colleagues noted a correlation between increased nighttime temperatures and suicide rates in the U.S. and Mexico. In tracking more than a billion social-media posts across multiple platforms from people living in varying climatic conditions, his team found that hotter-than-usual temperatures correlated with worse moods and an increase in reported mental-health difficulties. “If I were to say that climate change simply makes you grumpy, it doesn’t sound all that catastrophic,” Obradovich says. “But if grumpiness is one of myriad social changes that result, regularly, from unusually warm temperatures, we should be concerned about the cumulative effects of these changes over time on the long-term well-being of our society.”

Humans are incredibly adaptive, but when it comes to heat, there is a limit. When the ambient air exceeds the normal body temperature of 37°C (98.6°F), the only way to keep from overheating is by evaporative cooling—a.k.a. sweating. But when the humidity is high, sweating is less effective because the air is already saturated with moisture. As a result, the body’s core temperature increases, triggering a series of emergency protocols to protect vital functions.

First, blood flow to the skin increases, straining the heart. The brain tells the muscles to slow down, causing fatigue. Nerve cells misfire, leading to headache and nausea. If the core temperature continues to rise past 40°C to 41°C, organs start shutting down and cells deteriorate. Mora, at the University of Hawaii, described 27 different ways the body reacts to overheating, from kidney failure to blood poisoning when the gut lining disintegrates. All can result in death within a few hours.

Mora’s team analyzed data on 783 lethal heat waves spanning 35 years, in order to quantify which weather conditions posed the greatest mortality risk. It turns out the old cliché that it’s not the heat but the humidity holds true. Even relatively mild heat waves with daytime temperatures of 38°C to 39°C (100.4°F to 102.2°F) turn deadly when humidity exceeds 50%. In Jacobabad, it rarely does, but by 2100, some 74% of the global population will experience at least 20 days per year when heat and humidity reach that deadly intersection, according to some studies. The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates that increased heat and humidity has already reduced the amount of work people can do outdoors by 10% globally, a figure that will double by 2050. “I don’t think people quite grasp the seriousness of the situation,” says Mora. “An entire set of livelihoods depends on being outside. Imagine being a construction worker who can’t work for two months of the year.”

In Pakistan, evidence of a climate crisis is easy to find. For the past few years, Pakistanis say, every summer has felt hotter, every drought longer, and every monsoon shorter and later in the season. “Before, it used to be one or two weeks of 50° days,” says the nation’s climate-change minister, Malik Amin Aslam. “Now it is months.” These kinds of temperatures are not just deadly but also economically devastating. In a country surrounded by hostile neighbors, frequently targeted by terrorist groups and perpetually on the brink of nuclear war with India, Aslam ranks climate change as the “most severe existential threat facing Pakistan today.” His office estimates that climate change could cost the country anywhere from $7 billion to $10 billion a year in disaster response alone, never mind lost economic activity. And Pakistan is no different than anywhere else, he warns. “With a temperature increase of three to five degrees that we are now looking at, the survival of the world is at stake. We cannot run away from it.”

But to a certain extent, you can prepare for it. During the summer months, the Pakistani airwaves are full of public-service announcements warning residents about the dangers of heat, symptoms of heat exhaustion, and how to take precautions. Hospitals have dedicated wards for treating heat victims, and packets of oral rehydration salts can be found at any convenience-store cash register, next to the candy.

The only way to reduce heat waves would be to reduce global carbon emissions. But cities can make them safer by providing more green spaces. Anyone who has stepped under the shade of a tree on a hot day doesn’t need science to prove that it’s cooler, but according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the microclimate created by a few trees can reduce ambient temperatures by up to 5°C (9°F). Pakistani businessman turned environmentalist Shahzad Qureshi has taken that idea a step further by planting what he calls “urban forests” in the country’s two largest cities, Lahore and Karachi. He says these microparks help a city breathe, and serve as natural recovery wards from the urban heat-island effect. Right now Qureshi’s urban forests are privately funded, but he hopes they can become an example for smaller cities like Jacobabad, where government officials will see the benefit of growing urban forests over building yet another heat-trapping concrete behemoth.

In the meantime, Jacobabad’s Imam Medical Center sees up to 10 heat-exhaustion and heatstroke patients a day, a number head physician Hamid Imam Soomro expects to rise in the coming years. “People will have to find a way to adapt,” he says. “But some will die, especially the weak and the elderly.” He’s particularly worried about children, who often have to walk long distances without shade to get to school.

Even healthy adults can suffer the effects. Halima Bhangar, a 38-year-old widow who lives in a small village not far from Jacobabad, lost her husband to heatstroke in May 2018. He had gone to town to sell some cattle when he started feeling dizziness and heart palpitations. He went to a pharmacy to pick up some rehydration salts, but it was too late. He collapsed in the street. “It was the heat that killed him,” she says. “We were not aware of its repercussions.”

We had crowded into Bhangar’s one-room mud-brick house to escape the midday sun, and the heat was stifling. A solar panel propped up in the courtyard ran a ceiling fan that seemed to do little more than push the hot air around. I glanced down at the thermometer, which registered an outside temperature of 52.1°C, just a degree and a half shy of the country’s record high. Bhangar followed my gaze. “How can we protect ourselves from this heat?” she asked. “For how much longer can we survive here?” She has considered moving, but where in the world is immune from the rising temperatures? “We can’t run away from nature.”

This is one article in a series on the state of the planet’s response to climate change. Read the rest of the stories and sign up for One.Five, TIME’s climate change newsletter.